|

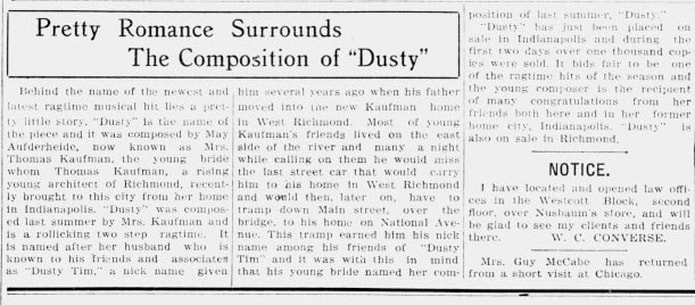

How are YOU celebrating May Aufderheide's 135th birthday? Perhaps you are wearing a big hat as May was wont to do (see above). As for me personally, I'm playing her "Dusty" rag from 1908 (see below). "Dusty" is a wonderful piece of ragtime. I particularly adore the second section that has "tailgate trombone" notes, propelling "Dusty" straight into the upper reaches of the rag-o-sphere. I always assumed that the title of the rag was a play on words. Dusty Rag. Get it? But it turns out that "Dusty" was May Aufderheide's fiancé's nickname. It says so in the newspaper. Here's the scoop, from the Richmond Palladium (Richmond, IN), April 17, 1908: So May Aufderheide's fiancé, Thomas Kaufman was also known as "Dusty Tim." He'd spend the night out with his friends, miss the last streetcar home, and would get home all "dusty" from the long walk. That explains "Dusty" but it does not explain why they called him "Tim." I suppose if Robert can be "Bob" and William can be "Bill," then Thomas can be "Tim?"

0 Comments

Back in 2006 I quit my day job and started hustling around town, playing piano wherever there was a piano to be played. One of my main gigs was at the Charlotte-Douglas Airport, where there was (and still is) a piano in the food court. One of the more recent Charlotte airport pianists. My airport repertoire was mostly loud and fast stuff because that got people's attention and brought in the tips. But from time to time I'd slow it down to relax the wary travelers who rocked themselves in the rocking chairs. Everybody Loves the Airport Rocking Chairs One of the songs I'd play for the rocking chair people was, of course, "Rockin' Chair" by Hoagy Carmichael. It set a peaceful mood, which was often appreciated. The airport gig had many enjoyable moments. People who liked the music would say hello to me, and interesting conversations often ensued. I had the pleasure of meeting the composer Richard Maltz who wrote an opera about Babe Ruth. I also met a professional Frank Sinatra imitator on his way to Vegas. And one person I met at the airport has remained a friend and I later played piano for his wedding. I don't play piano at the airport anymore, but I imagine it is a more difficult gig now than 15 years ago. Today, just about everyone has earbuds or headphones on, and folks who plop down on rocking chairs are usually engrossed in their screen. In 2006, the technology was a lot clunkier and people were still bored at the airport, so a piano player was a very welcome distraction. In 2023, our devices keep us endlessly preoccupied. A rhinoceros could stampede across the concourse and you'd miss it because you were watching Seinfeld on your iPad (with noice canceling earbuds on). But I suppose there are some advantages to playing airport piano in the iPhone era. If someone likes your music they can easily film it and share it. That could be a really good thing. It worked out well for this piano player at the Atlanta airport who got $60,000 in tips after a well-known motivational speaker posted a video of him on Instagram! Last summer I played Hoagy Carmichael's "Rockin' Chair" at the Lancaster Cultural Arts Center, which is a historic church converted into a concert venue. They have pews, not rocking chairs, but I think it worked out just fine:  In February 2022, I went to New Orleans to record a song for the AMC series "Interview With a Vampire." The film set was in the French Quarter, in the courtyard of a historic home formerly belonging to General Beauregard. I was not allowed to take photos, so here is an image from the internet: I spent many hours on the set and it was made clear to me that I had to be quiet. The production people would call out "Quiet on the set!" every time they were about to film a scene, which was pretty often. I did not want to find out what happened if you were noisy on the set. At one point, I heard faint drums and brass in the distance. Before I knew it, a small second line was marching down the street, right in front of the house. Needless to say, there was loudness on the set. But the filming did not stop for a moment. They just carried on as if everything was normal. So why were they were so insistent on having quiet on the set? If a brass band doesn't disrupt the filming, does one really need to be quiet on the set? And that reminds me, do you really need to turn off your cell phone on an airplane? I'm afraid I cannot answer these questions, I'm just a piano player. What I can do is pianistically recreate the experience of a marching band passing by. In fact, this was a common thing back in the early 1900s. There was a popular kind of march called a "patrol" that would start out quiet as a whisper, grow to a fortissimo by the middle of the piece, and as it neared the end, the music would return to a whisper and fade away. The point was to recreate the experience of a marching band passing by. Here is my pianistic re-creation of a New Orleans second line. A patrol, if you will. I present to you the New Orleans classic - "South Rampart Street Parade." Quiet on the set! First of all, according to the dictionary, Nonpareil is pronounced "non-pa-REL" (if you're American) and "non-pa-RAIL" (if you're British). It means "unrivaled" or "peerless" or as the sheet music below defines it -- "none to equal." A nonpareil is also a kind of candy and a kind of caper. Do not confuse the two, or you might end up with Chicken Piccata smothered in chocolate. A few years ago I podcasted about Scott Joplin's "Nonpareil" and the meaning of the word, but just now, upon seeing the Collins Dictionary definition, I realize I had missed yet another definition. Apparently, a nonpareil can also be a "painted bunting." Which is a kind of bird. Here is the male Nonpareil: And here is the original sheet music cover: That's a bunting alright...But not a nonpareil bunting. They got their buntings mixed up! Here's my theory on how this sheet music ended up with a flag-bunting on the cover: First: Joplin composed his rag and named it "The Nonpareil," but he did not intend it to be about buntings of any kind. Joplin surely used "nonpareil" as a superlative. In "King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and his Era," Edward A. Berlin points out that other musicians in Joplin's orbit were billing themselves as "nonpareil." Surely they were not calling themselves buntings. They were touting themselves as "none-to-equal." After Joplin submitted his Nonpareil (the rag) to the Stark Music Publishing Company, it was somebody's job to decide what to put on the sheet music cover. Somebody looked up "Nonpareil" in the dictionary, saw the "none-to-equal" and "bunting" definitions and decided to acknowledge both in the cover art. They put an American flag bunting on there, not realizing that the dictionary was referring to the bird bunting. Whoops! But it worked out fine. The scene on the cover, with Uncle Sam holding up the bunting, implies that the USA (and its flag) are none-to-equal. Clever! And a nice patriotic sentiment. It has nothing to do with a Nonpareil bunting, (which is a bird) and isn't what Joplin had in mind (which was neither a flag nor a bird), but hey, it still works. So that's my theory on how a bunting - but not a Nonpareil bunting - ended up on the sheet music cover. Behold, two types of buntings, but only one is a nonpareil: Now let's talk about the music, shall we? I love Joplin's "Nonpareil." I suspect that Joplin had a large ensemble in mind when he composed this. I say this because the second section (at 0:50 in the video below) has a wonderful left-hand melodic line that screams trombone section. I take the liberty of doubling the octaves to really bring out those trombones. Get out the bunting of your choice and tap your foot to "The Nonpareil:" I’m bringing back the blog! I just have so much to say about ragtime music. I can't hold it in any longer!

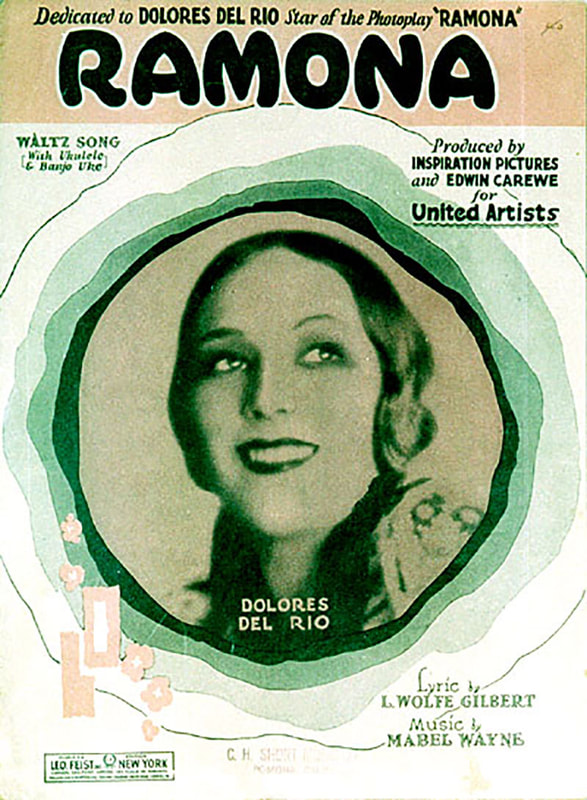

Its mid-November - which means its time to start getting ready for Christmas! This year I thought I'd spice up "Silent Night" by playing it in the style of Scott Joplin. Coming up with this arrangement was a bit challenging. If I played the melody with only minor embellishments, I thought it didn't sound ragtimey enough. But if I tweaked the melody too much, it wouldn't sound like "Silent Night" enough. So I had to find the right balance. Here is what I came up with: Cole Porter’s Love for Sale (1930) is about a madame advertising her services. I can think of lots of love songs in the Great American Songbook, but this is the only pay-for-love song I can think of. So Love for Sale is pretty unique. Due to its edgy subject matter, it was not played on the radio when it came out. And I think that’s reasonable, you don’t want impressionable 12 year-olds singing lyrics like: “If you want to buy my wares, follow me and climb the stairs” or “If you want the thrill of love, I’ve been through the mill of love.” Of course, those lyrics are wonderfully clever and sophisticated. So if I caught my 12 year old singing this song, I would give him only a light punishment. Actually….on second thought…...Who am I kidding? If I caught my kid singing Cole Porter, I’d be thrilled! I’d double his allowance. Here’s a song called "Whispering" (1920). It was originally credited to the songwriting team of John Schonberger (music) and Malvin Schonberger (lyrics). Later when the copyright was renewed, Richard Coburn was credited as the lyricist and Malvin Schonberger’s name disappeared, and Vincent Rose was added as co-composer. I don’t know what happened there, clearly there was some behind-the-scenes intrigue going on at "Whispering" headquarters. "Whispering" was the bee’s knees in 1920 when Paul Whiteman made it a big hit. Since then, it has remained a staple of the swing repertoire. It passed into the bebop era in the form of Dizzy Gillespie’s "Groovin’ High," which uses the chord changes of "Whispering." I like "Whispering" because it’s such a catchy little earworm. I also like the title. I try to play at least parts of the song extra quietly to evoke literal whispering. Before I was a full-time pianist, I was a librarian for two years. I’m not kidding. So I know a thing or two about whispering. As a pianist and former librarian I feel particularly well-suited to interpret this classic by the Office of Schonberger and Schonberger (or should I say Schonberger, Coburn, and Rose?). Anyway, I know Whispering so well that I can play it in any key, and I intimately refer to it not by its name, but by its Dewey Decimal number: 783.62W. My rendition is very much indebted to two of my favorite pianists, Teddy Wilson and Fats Waller. Teddy Wilson liked to walk tenths in the left hand and play slick clarinet-like single note lines in the right. Fats Waller liked to play things that...well….things that sound Fats Wallery. Its hard to explain. All I know is that I can’t seem to play a song for more than 20 seconds without a few Fats Wallerisms creeping in. One day, I decided it would be nice to spice up my repertoire with some Latin flavor. So I turned to the romantic Mexican-inspired waltz "Ramona," a massive hit from 1927, composed by Mabel Wayne. I was aware that "Ramona" was a hit movie in the 1920s starring Mexican actress Dolores Del Rio. The cover of the sheet music and various images from the film that I found on the internet, led me to assume that the movie was some kind of fluffy romance that takes place in old Mexico. Not having seen the movie, I concocted an elaborate arrangement of "Ramona" in which I incorporated various Latino melodies, like "La Paloma," "Cielito Lindo," "Leyenda" (by Albeniz), and of course, "La Cucaracha." I call this arrangement "Ramona Rhapsody Español."  Helen Hunt Jackson Helen Hunt Jackson I have been playing this arrangement of Ramona at many of my concerts for the past several years. I still haven't seen the movie. But I finally read Ramona - the novel from 1882, by Helen Hunt Jackson. This was what the movie was based on (and please do not confuse it with the Ramona Quimby childrens' books!). Upon reading the novel, I discovered that my assumptions about the "Ramona" story were way off. First of all, it technically doesn't take place in Mexico, but in California in the mid/late 1800s. But the main thing that I got wrong was that Ramona was no fluffy romance. It was intense. Here's my very watered-down synopsis: Ramona, who is raised as part of the old Mexican/California aristocracy, and Alessandro, a Native American, fall in love. They elope, and along with the rest of the Native American communities in California at that time, they experience grave injustices that make your blood boil. As part of the 1862 Homestead Act, Native American land was sold to white settlers, and the Native Americans were driven from their homes. They found themselves desperate and without means of making a living. Ramona and Alessandro have a baby, try their best to survive, but they are beset by tragedy. So, although "Ramona" is a lovely and pleasant tune, the story is dark, political, and outrage-inducing. I recommend you read the book. It has some great drama and romance, it paints an interesting picture of 19th century California, and you learn some disturbing and shameful aspects of American history along the way. But if you want to just close your eyes and think of romantic images of Spanish missions, orange groves, and pretty senioritas, please enjoy my rendition of this lovely song from 1927. Here’s my take on the old New Orleans standard, "Basin Street Blues:"  This tune has a rich and interesting history. Basin Street was in the heart of the New Orleans red-light district, known as Storyville. There were brothels up and down the street, and they had live music, so Basin Street was a great place for music. Say what you will about legalized prostitution - it fostered the environment in which jazz developed and blossomed. During WWI, the US Navy grew concerned that sailors on leave in New Orleans were getting a little too distracted. So the New Orleans City Council decided to criminalize prostitution. The legal brothels lining Basin Street closed down, and the jazz musicians had to seek their fortune elsewhere.  Spencer Williams Spencer Williams One of the musicians who left New Orleans was composer/pianist/singer Spencer Williams (1889-1969). Williams wrote “Basin Street Blues” when he was living in New York in the 1920s. For most songwriters, nostalgic songs about the south were pure fiction. They were usually written by northerners who hadn’t been south of Atlantic City. But “Basin Street Blues” was legit. Spencer Williams had actually lived on that street. When they closed down those brothels, Basin Street was renamed North Saratoga Street. But by the 1940s, “Basin Street Blues” had been immortalized by Louis Armstrong, and it was pretty clear that this North Saratoga business had to go. In 1945, native sons Sidney Bechet, Bunk Johnson, and Louis Armstrong returned to their hometown for a much heralded concert at Municipal Auditorium, and it was then that North Saratoga was officially changed back to Basin Street. Such is the power of music! |

Ethan UslanMusic, stories and thoughts from an old-time piano player. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed